The Manda Mine

From Miike to the mine entailed a journey of about half an hour by rickshaw, the way lying along roads through the paddy fields, passing small hamlets, where the advent of no less than four idjin san (Europeans) created no little stir and speculation. In the distance, the Manda Mine, the objective, was visible while the derricks, smoke-stacks and buildings of five other mines showed up plainly, or peeped over the shoulders of intervening hills. One mine, understood to be the Miyanohara, is operated by means of indentured labour, the operatives consisting of convicts, each of whom has been sentenced to a term of not less than ten years penal servitude.

The Miyanohara Mine

The Mitsui Co., it is understood, contracts with the Authorities for the supply of this labour, each convict engaged receiveing a settled, daily wage.

This money, however, is witheld and allowed to accumulate until the term of penal servitude is completed; thus Jiro, Taro or O Tsuke San - for, Alas! there are “lady-helps” - will have a considerable pay to “lift” or, the happy day when, purged of his, or her, offence, they may resume their place among their fellow freemen.

The discovery of the local coal deposits is attributed to a farmer, in the year 1469, shortly after which, work was commenced in a primitive way.

Nowadays, however, under the capable management of the Mitsui Co., the annual output is estimated at some 1,800,000 tons and the mines have been the property of the Company since their transfer by the Government in 1888.

A courteous reception was accorded the party on their arrival at the mine, one of the assistant managers receiveing visitors in a temporary office, the office proper being dismantled and in the hands of painters and decorators.

After partaking of tea, plans of the extensive workings underground were shown and explained to the visitors.

An immense amount of timber is used annually in these workings and to minimise expense an ingenious device has been adopted. A tunnel is excavated in the seam and this is afterwards filled, under pressure, with a mixture of sand and waste which is pumped into it. This latter on drying forms a solid shore of concrete, thus enabling the coal to be worked out on either side of it.

Getting the Coal

A gentleman connected with the office staff who spoke English, was delegated to guide the visitors on their tour of inspection and the first visit was made to the Pump Room, where five gigantic “Davy” pumps, three of which were at work, are installed, their huge, lattice-girder beams working back and forward majestically while a small river of rust coloured water rushed away from the discharge to plague the farmers in the vicinity.

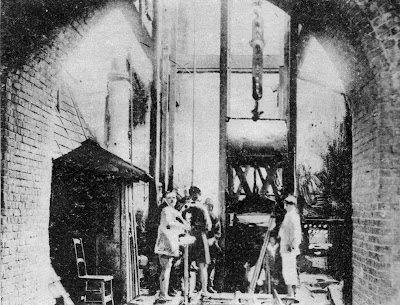

Pit-Head, Working Level

Next to the pit-head, where trucks laden with coal, or retured empties, are rising and falling day and night, week in and out.

It was gathered that the depth of the shaft of which there are three, one being reserved exclusively for labourers and materials, was 950 feet and that the cage with its two trucks, drops (or rises) this distance in forty seconds.

Underground, Bottom of Shaft

At this point, some discussion ensued and the pilgrim, ascertaining that a trip underground was in contemplation; began to sing (con expressione) “Ah! Don't go down the mine, Daddy,” which helped to persuade the one member of the party so desirous to remain above ground.

A visit to the Winding Room followed; in the outer one an emergency reel, upon which was wound a six inch steel hawser, was at rest, this being reserved for emergencies or for heavy weights.

The Winding Room

In the Winding Room, proper, are installed the large reels and machinery which operate the cables each of which passes out over the sheaves at the head of the derrick and down to the bottom of the shaft. Here steam is the motive power and, bearing in mind the extent of his responsibities, it is a case of:

“Don't speak to the man at the wheel.”

In the present instance, however, it is the man at the lever.

Behind each winding reel, with his eyes on the indicator and his hands on starting lever and reversing gear, stood one of these men and as the visitors watched, somewhere overhead an engine-room telegraph clanged. A small electric lamp lit up momentarily as the great reel began to revolve, winding in the wire hawser while in front, a dial, round which an indicator swung, showed the progress of the cage up the shaft a bell ringing and an automatic stop coming into play when the pointer on the indicator showed that the cage had arrived at the top.

Numerous safety devices abound to correct the personal equation, or an accident to the machinery. Accidents, however, are extremely rare, a fact which speaks well for the skill of the operatives and the care of the management.

It is which extreme gratification that the visitors note that, with one exception, the machinery throughout the mine, where not of Japanese construction, is the product of British engineering shops.

The exception referred to is the dynamo room and it is confidently anticipated that eventually the management will experience the demonstrations of the “cheap and nasty” that the Shanghai Municipal Council have had with their Boche-constructed electrical machinery.

At the pit-head (working level) the coal-laden trucks brought up the shaft and the empties going down work almost automatically. Double tracks of small narrow gauge railway, automatic checks and impulses with the use of gravitation; render manual labour unnecessary, beyond a general attendance to signals, or an occasional push, to start a car on its way down the track to the first weighing machine. At this latter point the truck stops automatically and while being weighed, the “card” of the party underground who have filled it is detatched from the truck and filed in the weigh-room, while the truck passes on to an automatic tip which discharges its contents down a chute, into the screening room, the empty truck continuing down a slope and round to the pit-head again, the last few yards (to check its momentum) being a sharp up grade, where it is assisted by an endless belt, having projecting spurs which engage and disengage themselves from the axle.

Down an iron staircase into the Screening Room. Here a terrific din prevails, the screening machinery making so much noise that a knowledge of “lip-reading” is absolutely necessary if one would converse with his fellow-man.

The Screening Room

Here the coal, tipped from the trucks above first passes over a sifter an arrangement resembling the moving fire-bars of an automatic stoker; this allows the dust to fall into another department where it is made into briquettes. The lump coal passes to a broad endless belt made of iron plates the clatter and clang of which is the cause of the infernal din.

On each side of this conveyer stand a number of women and girls, who select the coal as it passes before them and pick out the lumps of shale, stone &c., and throw them into receptacles provided for that purpose.

The remarkable absence of dust enables these girls to keep themselves clean even at such work as selecting coal, their hands only showing evidence of their labours and their head towels with which they protect their hair and the bright colours of their kimonos, present a pleasing aspect in this noisy inferno.

After leaving the screening room, the coal is again weighed and loaded on trucks, ready for its trip to the coal tips at the Dock.

American Transport "Dix"

In the Lamp Room which was next visited, the thousands of lamps in their racks and the large staff of lamp-trimmers, indicated the large number necessary for the operation of the mine, especially as the lamps in use by the shift at work underground were, of course, absent.

Many of the working galleries underground are lighted by electricity but the portable lamp used by the miners seems to be a type of the “Geordy” lamp, instead of the “Davy,” as used in British collieries. A light, volatile oil is used and each lamp is fitted with an electric switch at the bottom, by means of which the closed lamp may be relighted, should it accidentally be put out.

The Dynamo Room, in which a large ventilating fan is installed, was not visited. Respect for their watches entailed the visitors keeping a respectable distance from the numerous dynamos. Most of the machinery also, being of Boche manufacture, it consequantly, did not interest the visitors.

In the Boiler Rooms, a battery of 19 Babcock and Wilcox W. T. boilers, each with rotary fire-bars and automatic stokers, supplements the 14 large Lancashire boilers installed in an adjacent building.

An interesting feature in connection with these Lancashire boilers is the fact that they were brought out to Japan by steamers of Blue Funnel Line to Nagasaki, where they were discharged into the water, to be floated round to Miike by tug-boats. One hundred and twenty firemen on three shifts are employed at this mine.

The mine itself gives employment to some 4,000 operatives of both sexes. Work underground, getting the coal, is carried on by partnerships of six, frequently such partnership consisting of a man, his wife and children.

A Family "Partnership"

Coke of an excellent grade is made at the large coke-ovens installed near the mine, a network of overhead cables conveying coal or coke to or from the ovens. On returning to the office, the afternoon shift was observed coming up from their work underground. From the shaft the miners of both sexes proceeded to the large bath-houses maintained by the Company where, after a hot bath and a change to their above-ground clothing, they proceed homeward, looking so clean and fresh that one can scarcely credit the fact that they had been toiling underground for the preceding twelve hours.

No comments:

Post a Comment